The formula for calculating ROI is so simple that I’ll share it right here, in the article introduction:

((Return from content − cost of content) / cost of content) * 100If your content marketing generated $10,000 in sales and cost $2,000 to create, that’s an ROI of 400%:

(($10,000 - $2,000) / $2,000) * 100 = 400%Although the math is simple, actually doing this exercise in real life is tricky, for a few reasons. The most important: it’s pretty hard to put a dollar value on every single benefit of your content marketing.

I’ll explain why, and then show you 3 practical methods for quickly working out your content marketing ROI.

If you want to talk convincingly about ROI to your boss or your clients, it helps to understand these three points:

If all of your content marketing is outsourced from freelancers or agencies, it’s relatively easy to work out how much it costs: it’s the amount they bill you.

If you have an entirely in-house team, with team members dedicating 100% of their effort to content, costs are similarly straightforward: it’s their salaries.

But things can get a little complicated if you source content from multiple sources (like a combination of freelancers, agencies, and in-house team members), or if multiple people contribute to your content in relatively small ways (like a designer dedicating a third of their time to content, and two thirds to product marketing).

But this is still simple compared to our next complication:

The most obvious benefit of content marketing: it attracts new customers. We can theoretically add up all the new customers who found and bought our product because of our content marketing, and work out how much money they spent (I explain how in the next section).

But content has lots of other benefits that are less easy to measure. It can:

- Encourage upsells and expansion. By sharing product tips and new use cases, content can provide the nudge needed to turn free users into power users, or “Lite” plan customers into “Advanced” plan users—like My 5 Favorite Ahrefs Use Cases for Content Marketers.

- Save money on customer support. Content can help answer customer questions before they become support queries, like the many guides we’ve published to help users understand how metrics like Traffic Value are calculated, and how they can be used.

- Build brand recognition and affinity. Content can give your brand a voice, sharing the motivations and beliefs that underpin the products or services you sell. We generally like to buy from companies we respect, so “brand affinity” can make a real difference to the bottom line.

- Makes paid search advertising more effective. Sending paid search traffic to articles instead of “traditional” landing pages can reduce the cost of clicks (something we’ve done for articles like our guide to keyword research).

- Help other pages perform better. A page that generates a ton of backlinks but no sales (like our list of SEO statistics) can still contribute to revenue by helping other “money” pages rank better for their target keywords.

Many of these benefits are virtually invisible—how do you measure support queries that content stopped from existing?—but very real. No matter how you calculate ROI, there’s a good chance you’ll be undervaluing its impact.

Which brings us to our next complication:

Working out the role content played in a sale is called “attribution”, and it’s pretty tricky to pin down.

Did someone convert because of an article or in spite of it? When they read multiple articles, which had the biggest impact? If someone buys because of an advert, should we still credit the blog post they read beforehand?

Customer journeys are also rarely as straightforward as we’d hope. One person might read 50 articles and never buy anything; another might read a single article, disappear for a year, and immediately buy. What role did content play in those journeys?

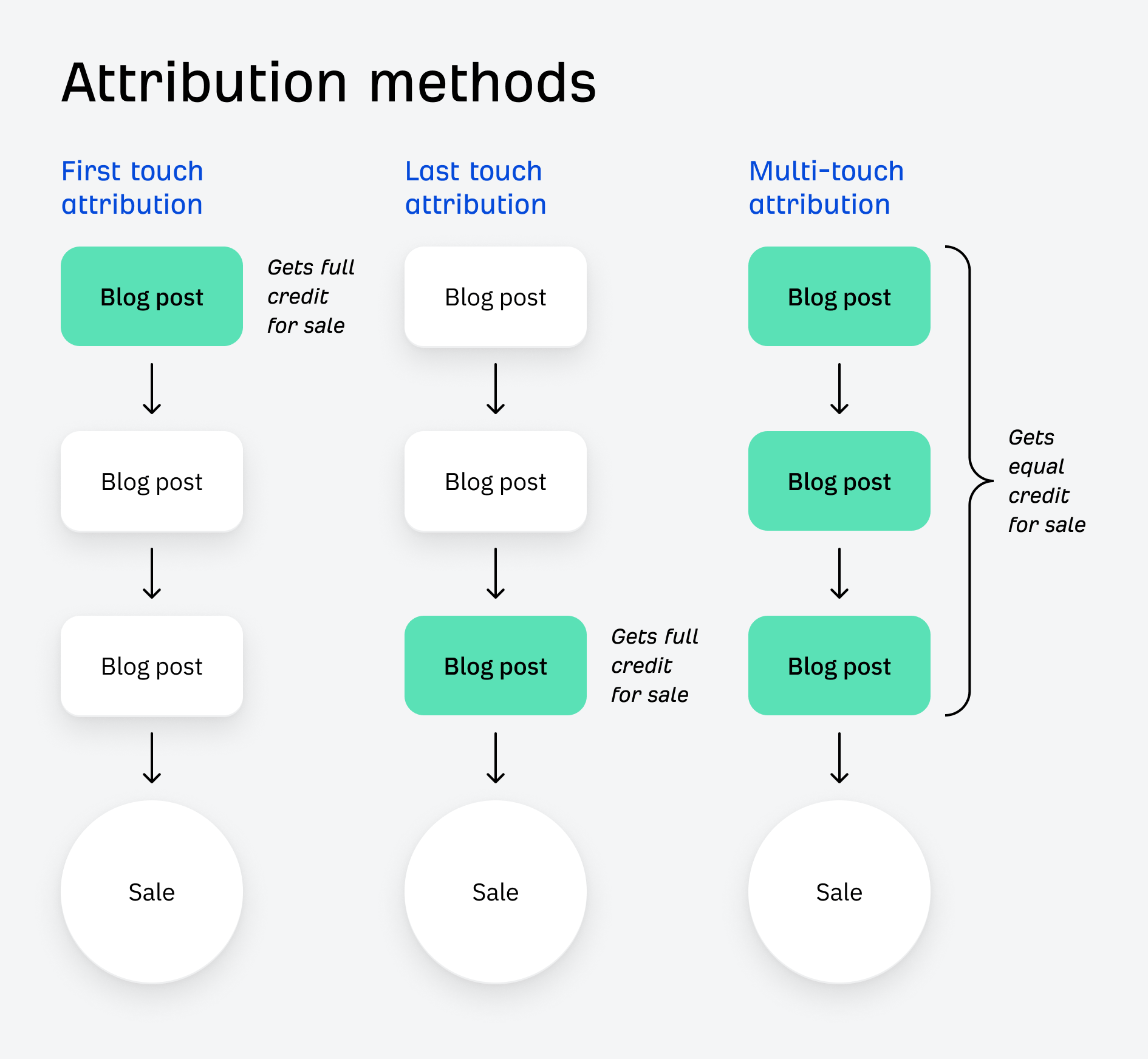

There are different ways of measuring attribution to help with some of this uncertainty:

- First-touch attribution credits the first piece of content a visitor engages with before converting.

- Last-touch attribution credits the last piece of content.

- Multi-touch attribution tries to credit every piece of content that was involved in the buying process.

But in all cases, attribution is never perfect: we just can’t measure every interaction someone has with our content.

In a perfect world, we would know exactly how much revenue each and every blog post generated for our business. To calculate ROI this way, we can use a formula as follows:

Return from content marketing = (New customers from content * ACV)

To work this out, we need to calculate the number of new customers generated by our content in a given period. If you don’t know this figure, you’ll need to set up some kind of conversation tracking in software like Google Analytics, allowing you to track the number of people that complete a desired action on your blog post (like filling in a form or starting a free trial)

In most cases, visitors won’t buy directly from your blog post, so you’ll need to track:

- The number of conversions generated by your content (e.g. free trial signups or demo requests), and

- The number of those conversions that went on to become paying customers.

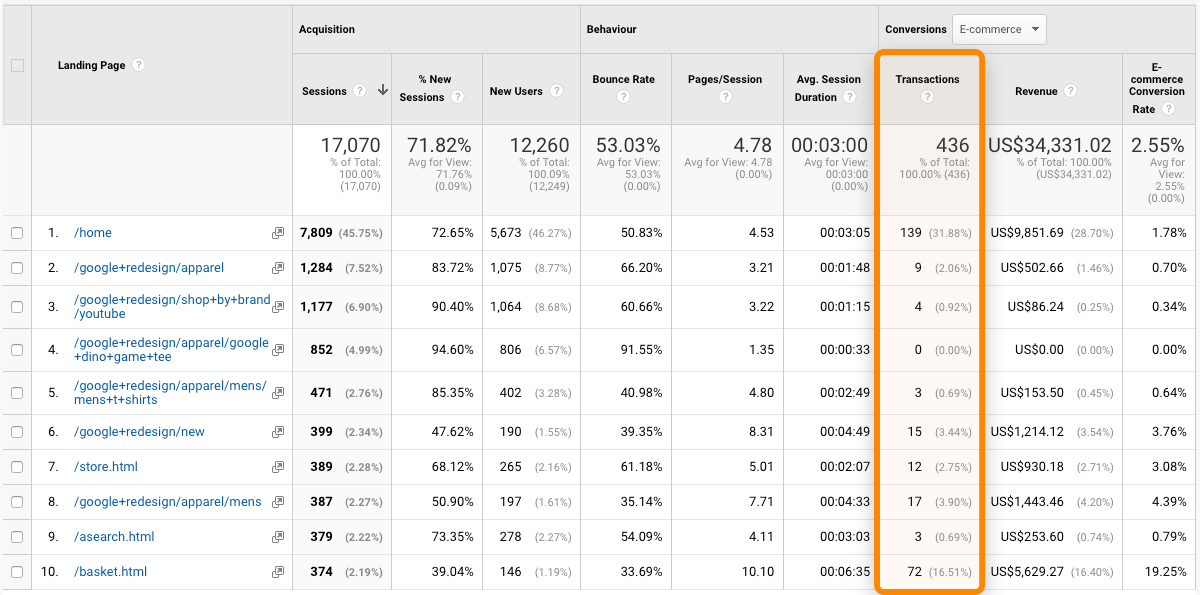

In the image below, we can see which pages visitors land on before purchasing a product. We can also see the conversion rate and the revenue attributed to the conversions:

Next, we need to calculate ACV: average customer value. This refers to the typical amount that customers spend with our company over the course of their relationship with us.

If we sell one product, and most customers buy just once, our ACV will be the price of our product. If we offer multiple products or add-ons, and customers buy regularly or set up subscriptions, then our ACV will be a lot higher.

Let’s assume that our conversion analysis shows that we had 1,000 free trial signups from our content in February, and 100 of those free trials became paying customers. If our ACV is $2,000, we can plug these numbers into our formula to calculate a return from content of $200,000:

(New customers from content * ACV) = 100 * $2,000 = $200,000This method is the gold standard of ROI calculations, but (because of the problems mentioned above) calculating ROI like this can be extremely complicated.

At the other end of the spectrum, here’s a quick and easy method that takes about 30 seconds using Ahrefs:

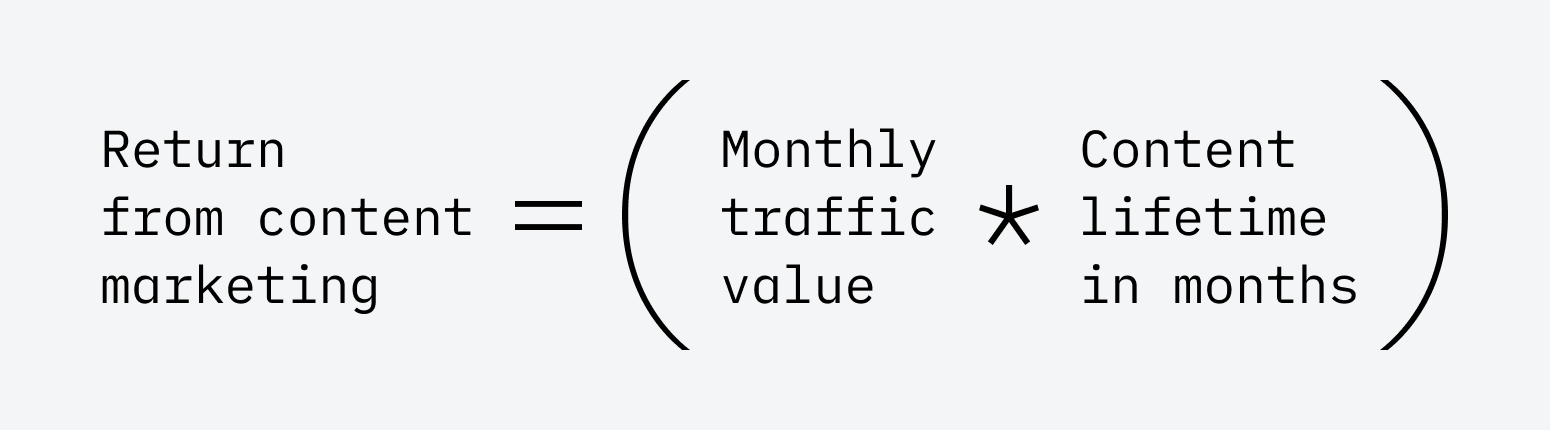

Return from content marketing = (monthly traffic value * content lifetime in months)

Instead of working out how much revenue we’ve generated from our content, this method estimates how much money we’ve saved by ranking organically for keywords instead of paying for advertising.

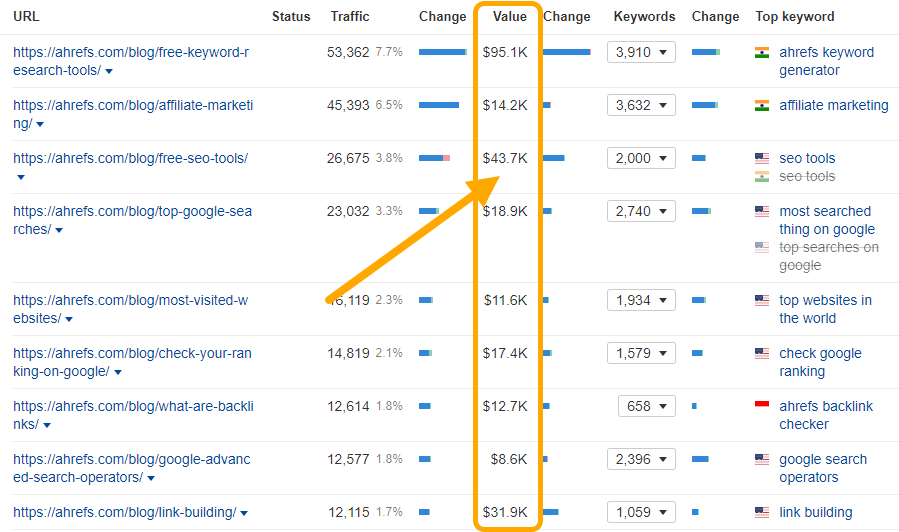

In Ahrefs, you can estimate the Traffic Value of any article—the amount it would cost to generate the same traffic via Google Ads, instead of SEO.

Below, we can see that it would cost an estimated ~$44k to “replace” the traffic to our list of free SEO tools using ads:

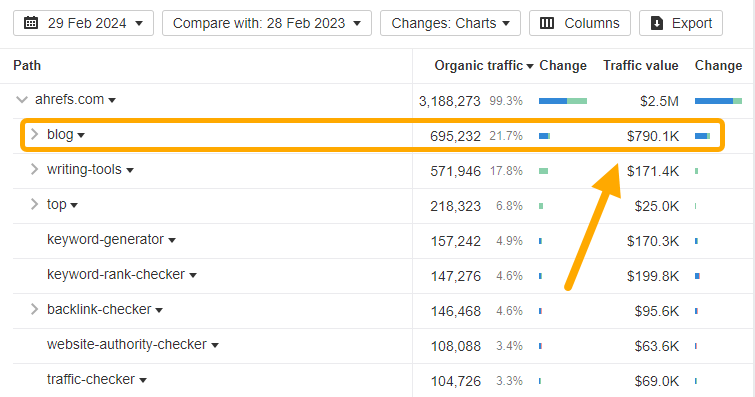

If we add up the traffic value of all the pages in our blog, we have an estimated monthly traffic value of $790,000:

Put another way, if we used paid advertising to get the same amount of visits from the same keywords, we’d need to spend around $790,000 on ads, each and every month.

Most content is useful for longer than a single month, so we can multiply this monthly traffic value by the expected useful “lifetime” of our content. If we use two years as a starting point, that gives us a lifetime traffic value of $18,960,000:

(Monthly traffic value * content lifetime) = $790,900 * 24-months = $18,960,000We have over 2,000 blog articles at Ahrefs, and we were probably never going to spend $19 million on paid advertising. But this calculation allows you to assign a dollar value to your content in a matter of seconds. It’s particularly useful if your company recently switched from a heavy reliance on paid advertising to content marketing, letting you show off the money you’ve saved from the switch.

Let’s wrap up with a best-of-both-worlds approach, very similar to how we calculate ROI at Ahrefs:

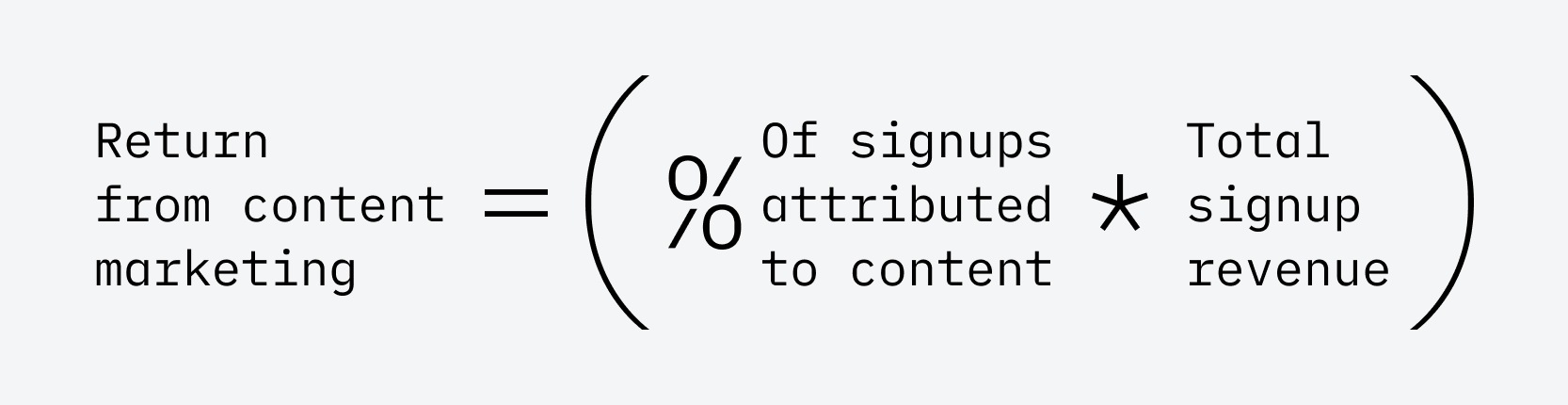

Return from content = (% of signups attributed to content * total signup revenue)

Whenever a new customer signs up for Ahrefs, we ask them a question: Where did you hear about us?

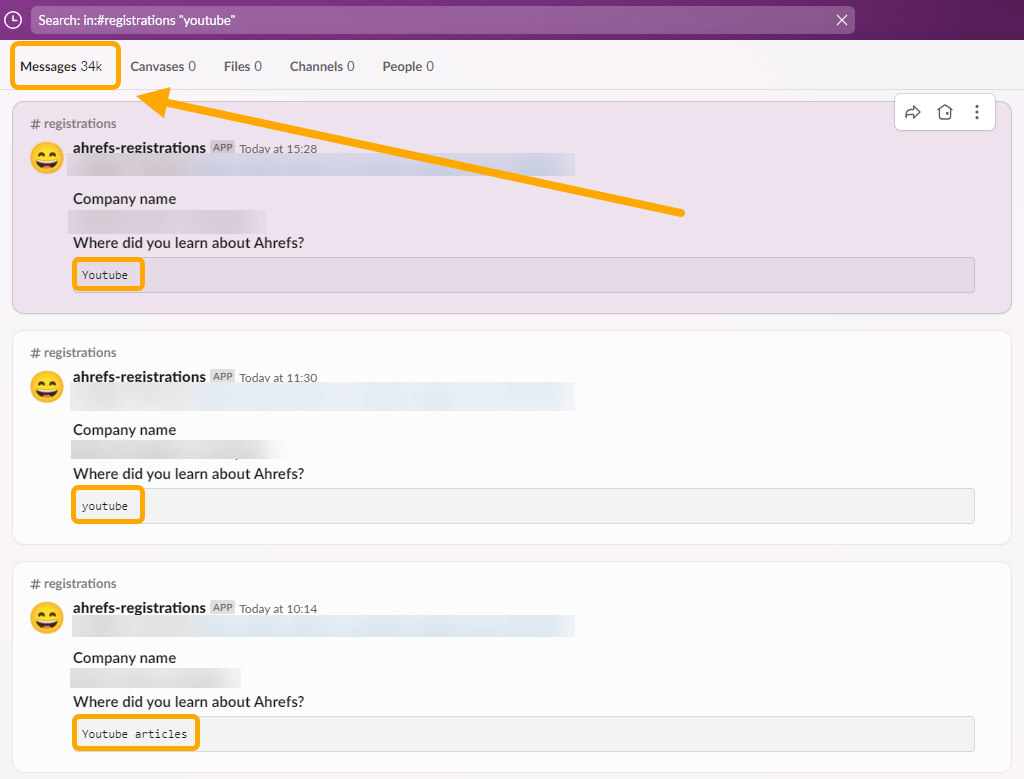

Their answer is piped into a dedicated Slack channel, #registrations, which gives us a live feed of new signups and, crucially, how they discovered Ahrefs. Sam, our VP of Marketing, regularly uses this feed to work out the percentage of total signups that can be attributed to his YouTube content.

If I head to #registrations and run a search for signups that mentioned “youtube”, we can see over 34,000 people that directly attributed their discovery of Ahrefs to Sam’s video content:

We can use this to estimate content marketing ROI: if 33% of all respondents in a given month attribute their signing up to YouTube, it would be fairly reasonable to assume that 33% of all signups came from YouTube, and that 33% of all new revenue should be attributed to our video content efforts.

If we assume a theoretical monthly revenue of $300,000, and that 1,000 of a total 3,000 signups could be attributed to “YouTube”, we can plug these values into our formula for a return on content of $100,000:

(33% of signups attributed to content * $300,000) = $100,000This method will underreport the number of signups generated (people might misspell YouTube, or say “videos” instead, or most likely, not answer the question at all). The relationship between new signups and new revenue might also be more complicated than we assume here (if you have lots of free users, for example).

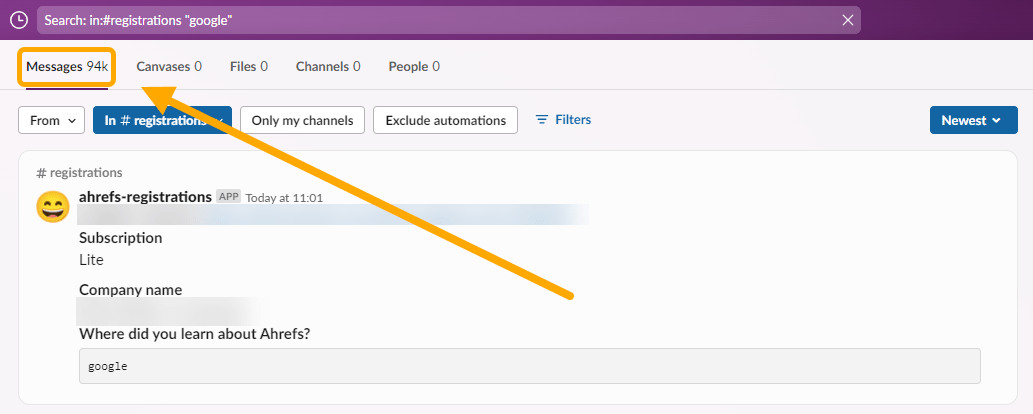

But it has the benefit of making it easy to compare to other marketing channels. If I search for “google” in the same #registration channel, I see 94,000 mentions—bigger than Sam’s 34,000 YouTube mentions:

(Although he’s definitely catching up…)

Final thoughts

There are tons of ways to measure content marketing ROI, and none of them are perfect. But for practical purposes, they don’t need to be.

Metrics, like content marketing ROI, are most useful as directional indicators. Instead of obsessing over perfect calculations, it’s better to choose a simple methodology, stick to it consistently, and see how it changes over time.

![How to Optimize for Google’s Featured Snippets [Updated for 2024]](https://moz.com/images/blog/Blog-OG-images/How-to-Optimize-for-Googles-Featured-Snippets-OG-Image.png?w=1200&h=630&q=82&auto=format&fit=crop&dm=1724004002&s=13df73104762982790dab6dc8328023f)